Are They Fiberglass Boats Anymore?

by David Pascoe

(Caution: This page has a lot of pictures and will be slow loading.)

Not long ago I was the recipient of a rather distressing revelation.

It happened when I was asked by a client to attend an auction of storm damaged boats here in Fort Lauderdale. There were two minor hurricanes and one tropical storm in Florida last year, but other than to trees, I wasn't aware of much damage having occurred. In fact, during one of the hurricanes, I was out there with a video camera filming what was going on at several marinas. Not much, except for a few people that did nothing to prepare. Mostly it was these people's boats that ended up in the auction.

Arriving at the auction site, a large open field filled with damaged boats, numerous damaged small boats immediately caught my interest. In part, this was due to so many of them appearing as though they'd been caught in a monster storm like Andrew, instead of a bottom of category one storms with winds barely over hurricane strength, 74 mph. A salient point here is that we have no large, open expanses of water. Just canals and rivers. So, with a storm surge of only 18 inches at high tide, I was scratching my head about why so much damage.

Here's a sampling of the various materials that were found within the broken up hull sides.

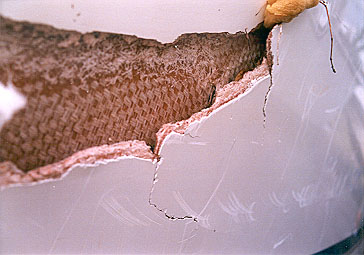

Here's fine illustration of what is meant by the laminate being comprised of an extremely small amount of fiberglass reinforcement. The only glass you see here is a single layer of Roving on the inside of the hull, with the exception of a very, very thin layer of mat against the gel coat. Otherwise, the major part of this Sea Ray hull is comprised of some kind of very porous material. Notice how huge chunks have broken away. This would never happen with fiberglass laminate.

Secondly, so many of these boats had degrees of damage that I hadn't seen before, even from major storms, yet alone minor storms. Much of the damage that I observed seemed to have occurred under different parameters. By that I mean that, in order for a fiberglass hull to become completely broken up, usually a great deal of prolonged bashing and battering against other hard objects is required. Usually a busted up hull will display extremely heavy battering as revealed by heavy gouging and many impact points on the hull. What was startling about these boats were that so many of them were busted up without revealing heavy battering.

Or, to put it another way, these boats got broken up by only a few heavy impacts, and not hours worth of sustained battering. In several of my articles on the subject of construction, I have a photo of a 42 Bertram that broke loose during Opal (1995, Florida panhandle) and was badly battered against pilings and other objects for many hours. The hull laminates did not fail, but obviously had sustained a horrendous beating. I used those photos as a good example of just how strong an ordinary fiberglass laminate can be.

What was so eye-catching about these boats is that many of the broken up pieces did not show any significant degree of heavy battering. The analogy here looked more like hitting a glass bottle with a hammer -- it only takes one swing to break it.

Thirdly, what next caught my attention, and what I found truly distressing, was that these damaged boats revealed what they were made of. Simply put, whatever these materials are, I didn't recognize many of them. And, I suspect that in looking over these photos, you won't either.

Of course some would say, "Hey, you're a surveyor. You're supposed to know these things." Right. But we don't stand there watching thousands of boats being built, and neither do we (unless we're willing to be mislead) take the builder's word for it. The observation of busted up hulls, as we have here, is how we find out. Unfortunately, we don't often get the opportunity to do that.

* * * * * * * *We talk a lot about core materials on this site because coring things like hulls and decks has, over the years, proved troublesome. There have been too many problems with materials like foam, especially delaminations and incomplete bonding of the outer skins.

But now we have something new entering the scene, something they call "advanced composites." A composite refers basically to two or more materials that are bonded together. If you glued a piece of wood and plastic together, technically that would be a composite. A balsa cored deck is also a composite, though most of us would just as soon call it cored construction because we know what that means. When the marketing people say "advanced composites," well, we don't know what that means since it could be anything, which, judging by what I saw and the photos displayed here, it does mean just about anything.

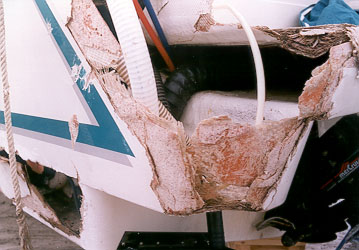

Here we see a big chunk of hull side that is quite simply gone missing. Notice that the puncture hole is at the bottom of the photo. This shot gives an excellent indication of the strength properties of this "advanced composite."

This photo further illustrates the strength of the bond between this outer skin, and the putty core. Notice that I easily hold it away with my fingers. After taking the photo, I took hold of that edge and just tore the entire outer skin of this boat off, comprising four feet of undamaged area. Notice how easily this material cracks.

The first question to cross my mind was, "Can these fairly be called fiberglass boats any more?" What we see here are hulls made with increasingly less and less fiberglass, and more and more of something else. Some of these boats were stunning in the limited amout of structural fibers used.

One good example is a Sea Ray where the hull side had ONE layer of woven roving, two thin layers of chopped strand mat, and all the rest of the laminate was some kind of brittle putty.

Woven roving is a cross weave fabric of glass fibers on a 90 degree axis. Each bundle or thread of fibers is rather wide and slightly oval shaped. As a fabric, it is rather coarse, and is never used against the gel coated side of a laminate because the weave pattern would show through. Roving is a general purpose fabric that has severed the industry very well. Nearly all boats built prior to around 1992 use it exclusively. Compared to all types of glass material, it has moderate, all-around strength. The most common is called 20 ounce roving because it weights 20 oz. per square yard.

In another boat, only two layers of mat were separated by an expanse of putty. No STRUCTURAL fiber at all, just very weak mat. I had no doubt that if one swung a carpenter's hammer at the side of this hull, the hammer would go right through.

What do I mean by putty? Well, the material looks just like fairing material (some call it bondo, if only because it resembles that automotive repair material). I've never seen this before, though the Sea Ray in question goes back to the early 1990's. Plenty of this material was exposed. Taking pieces in my hands, I could easy crumble the stuff between my fingers. It's not foam, it's not Coremat, and it was found in colors of gray, pink and tan, each in different boats.

What we see here really begs the question, for glass fibers make up only a small percentage of the total laminate thickness, which, as you can see, is pitifully thin to begin with. How about a hull side on a 27 footer that is 3/16" thick, with 2/16" of it being this putty material? That means there was only 1/8" of glass that included the gel coat. Could this leave any doubt about why so many of these small boats got busted to pieces in a minor storm, in a place where there was almost no storm surge? Not in my mind, anyway.

Yet another notable factor was the massive disbonding of the pitiful amounts of glass from the putty -- or call it a core if you're so inclined. Check out the photo below where I grabbed a piece of the outer skin and tore the whole thing off with minimal effort. In this case, the outer skin consisted of two layers of mat (I think). The bonding to the putty was nearly zero on both inner and outer plies. Notice how it breaks away on both sides of the "bond." Notice how easily the stuff cracks and breaks out.

I'm not sure what the point of all this is. Frankly, I'm still so shocked by what I saw that I've yet to fully digest the significance of it. These examples were not confined to just a few boats, but covered a fairly wide range of builders. And most significantly, of the boats which were built with solid fiberglass construction, I did not find one that was busted up anywhere near like these "advanced composites." Not one. There were some old Bayliners and Mainships (1970's) that were badly battered, but none were broken up. A few cracks maybe, but mostly heavy gouging and battering.

If this is the state-of-the-art production boat building, it's a rather pitiful state much of the industry has come to. I find it very hard not derisively call this stuff "the hamburger helper of boat building." What I saw is beginning to explain some of the more common symptoms we see in boats that are starting to come apart. Things like deck joints coming apart, heavy cracking along toe rails and chines, bulkheads, stringers and frames breaking loose, window frames that won't stay sealed, and heavy stress cracking occurring in places that it shouldn't.

Never mind what these materials may be doing for the blistering problem. Why talk about high quality resins when most of the hull material consists of some unknown material?

What concerns me most as a surveyor though is that we have been calling these things fiberglass boats when, in fact, fiberglass may be only a minor ingredient. How can you call it a fiberglass boat when only 10-20% of the total is glass? Previously, we'd look at a hull and question whether it was just cored or not. Now it seems we have to question the entire matrix. What is it made of?

Need to see more? How about this one? Here's the 3/16 or maybe 5/32" laminate referred to. Where's the beef? Imagine that this is all that's separating you from the deep blue sea.

Notice the nature of this puncture wound. The impact simply breaks a chunk of the laminate out, then separates the silly putty from its single backing of roving. And then the cracks that radiate outward. It's the lack of long fibers that accounts for this result.

Well, in the case of the photo below, appearances are misleading. If you look at the inside of the hull, what you will see is a surface made up of woven roving. The misleading part is that that is the ONLY layer of roving, with the remainder of it being some other stuff. If the surveyor called it a fiberglass boat in his report, he'd be wrong, and could be sued for his error. Unfortunately, short of cutting holes in the hull, he has no way of determining otherwise. Seeing that one layer of roving on the inside, I would likely make the same mistake too.

This view gives a better overall understanding of how large areas of a hull simply break out under impact. This is the platform extension of a 30 footer. Note the break out in the chine at lower left. With a strength factor like this, a person could reduce this boat to a pile of pieces with a carpenter's hammer. Also notice that there are NO STRUCTURAL GLASS REINFORCEMENTS showing in many areas of this broken up hull.

What's even worse is that you have to wonder if the builder did it that with the intent on misleading the observer. Roving is much stronger than mat by several magnitudes. For strength purposes on a composite, you'd put the roving on the outside, not the inside. Hence, it's hard not to come to the conclusion that the roving on the inside is, indeed, intended to mislead.

* * * * * *One conclusion we can certainly come to is that the strength and impact resistance of boats built with these materials is something worse than merely inadequate. In the past, it was generally true that no matter how low cost the boat, a decently laid up solid laminate hull was capable of surviving a heavy beating without the hull breaking into pieces as we see here. As near as I can tell, the boats shown here received a minor beating, and broke to pieces. How can there be any doubt of that when the major part of the laminate is nothing but putty?

It has always been the case that when a surveyor calls a boat "fiberglass," he's making an assumption -- an article of faith based on the fact that there were no other materials being used other than standard balsa or foam cores. Now we have a new paradigm. Enter a whole host of new materials, of which no one knows anything about, but for which we are getting some pretty good indications that many of them leave a lot to be desired.

Yet all of this still begs the question of how we should refer to the hull material of these boats. I know one thing for sure: I'm going to stop calling them fiberglass reinforced plastic. For that they surely are not. I can also state with confidence that this is going to have profound implications on all aspects of boating, including owners, surveyors, insurers and, of course, the builders themselves.

Without knowing it, we have apparently entered the era of the Putty Boat.

Fiberglass reinforced plastic. This is the full name of what, for over forty years, has been known as the fiberglass boat. It consists of a basic standard of 65% continuous glass fibers, in the form of fabrics, and 35% plastic resin. As you can see from the above photos, none of these boats meet that description. During this period of time, the fiberglass has consisted of fabrics of woven, continuous fibers. The length of some of these fibers can be as long as the boat. These fibers, much like the huge cables that hold up suspension bridges, rely upon the continuous lengths and orientation of the fibers for their strength. Today, there is a large variety of weaves available, but they are all essentially weaves of continuous fibers.

In the early years of small FRP boat building, a few companies tried making boats from chopped strands of fibers, mixed with polyester resin and blown through a gun into a mold. The length of these fibers was about 3-4 inches and were usually curled like cut hair when viewed in the mold. Very quickly we learned just how weak laminates made with short fibers are. Those "blow-molded" boats tended to break up all to soon. The chopper-gun boats soon disappeared from the scene. Today, things like shower stalls, truck fenders and the Corvette automobile body are made with chopper guns because they don't require great strength like a boat hull. For this reason, chopped strand is not considered as a structural fiber.

That does not mean that chopped strand mat and chopper guns have disappeared from boat shops. Chopped strand mat (CSM) is still used on all boats to prevent the weave pattern of fabrics like roving from showing on the gel coat surface. A very thin layer of mat is also used between heavy fabrics to prevent concentrations of resin between the heavy fabrics. And for other uses where very high strength is not required. One of our complaints about Taiwan boats has always been that they make use of the chopper gun too much.

Yet another problem with CSM is that it wets out with resin poorly and is well known to be very porous. The use of excessive amounts of CMS and chopper gun has been directly linked with blistering that originates within the CSM, as opposed to just being under the gel coat.

What you see in the above photos is even worse, for there is far less fiber in these than in a blow molded boat. This is what accounts for the severe breakouts of large sections of the hull. Quite simply, there is no fiber reinforcement, and the single layers of roving that you see on the inside serve no better purpose than trying to put a thin sheet of steel onto a spun fiber blanket in order to make the blanket strong. The steel would impart no strength to the blanket.

Aside from that issue, to use a hard, brittle material such as we see on these boats suggests that at every point a hull side sustains an even minor impact, that putty-like stuff is going to crack. Such cracks may not show on the outside, but may remain hidden beneath the surface. In time, with repeated stress cycles, one has to wonder about the whole matrix breaking down. Not to mention such issues as water absorption and retention along with subsequent chemical changes that may occur.

Even worse, when we now look at a given boat, we can no longer take for granted what the hull material is. We simply have no way of knowing. That leaves us all in the dark. Call me a Neoluddite if you wish (the 19th century English society that opposed the industrial revolution), but my worst fears about "high tech" materials in production boat building have become a reality.

Posted January 12, 2000

Visit davidpascoe.com for his power boat books

Visit davidpascoe.com for his power boat books

David Pascoe is a second generation marine surveyor in his family who began his surveying career at age 16 as an apprentice in 1965 as the era of wooden boats was drawing to a close.

Certified by the National Association of Marine Surveyors in 1972, he has conducted over 5,000 pre purchase surveys in addition to having conducted hundreds of boating accident investigations, including fires, sinkings, hull failures and machinery failure analysis.

Over forty years of knowledge and experience are brought to bear in following books. David Pascoe is the author of:

In addition to readers in the United States, boaters and boat industry professionals worldwide from nearly 80 countries have purchased David Pascoe's books, since introduction of his first book in 2001.

In 2012, David Pascoe has retired from marine surveying business at age 65.

On November 23rd, 2018, David Pascoe has passed away at age 71.

Biography - Long version