Chine Riding

How Hull Shape and Weight Affect Performance

by David Pascoe

During the last six months, I've sea trialed more large expensive center console boats than ever before. The reason is that more and more builders are offering CC boats that are getting bigger and always more expensive. No surprise there, but what is surprising is the poor performance of some of these boats, boats ranging in price from $70 thousands to well over $150K.

At prices like that for an open boat, one would expect superior performance. Yet superior performance was not what we were seeing. Instead, many of these boats performed no better than a typical family cruiser or runabout. It's one thing when the Rinky-Dinky 260 GSLT-X flops over on its side and stays there at cruising speeds, or it pounds and slams in an 18" chop enough to jar your teeth, but you don't expect that with what is ostensibly a high end sport fisherman.

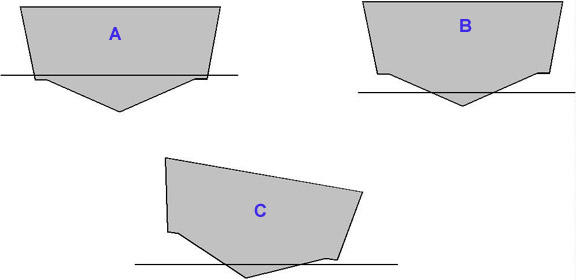

(A) Normal trim at rest; (B)

Flotation level at speed; (C) the result of imbalance.

(A) Normal trim at rest; (B)

Flotation level at speed; (C) the result of imbalance. Case in point: Five of the last six twin engine CC boats we've tested chine ride. The sixth one also did, but was generally controllable with careful steering. The others would ride on one side of the hull or the other no matter what you did with wheel, engine trim or trim tabs. In most cases, playing with trim controls only made the situation worse, so what we'd do is start out with all trim controls in a neutral position, meaning tabs fully retracted and engines carefully set identically level before starting out.

No joy, the boats went through their flop over routine no matter how hard myself or anyone else tried to prevent it.

Chine riding is a problem that occurs with deep vee hulls. In years past it was fairly rare, but as boats keep going faster and faster, and as builders keep making boats lighter and lighter, the problem has become widespread across a wide range of boats, from family cruisers to even large sport fishing yachts. Why is this a serious problem? Mainly because a hull listing strongly to one side while traveling at high speed is hard to control, and can be downright dangerous. Aside from the fact that it is not pleasant riding in a boat that is listing twenty degrees or so.

Chine riding as a phenomenon is caused by design errors. It is an error because it is preventable if the designer knows what he's doing. The illustrations I've included here clearly show why it happens. With a deep vee hull, the faster it goes, the more the hull is going to rise up out of the water. In fact, by the time a hull is going 40 mph, chances are that the hull is riding only on the apex of the vee, so that unless one is steering the boat perfectly straight, the boat is going to flop over onto the flat part of the bottom.

Or, if the boat is slightly heavier on one side or the other, the imbalance will cause it to want to flop to one side most of the time. Of course, there are differences between single and twin engine boats. On smaller, single engine outboards, propeller torque may cause it to flop to one side only. The opposing rotation of two props provides a greater degree of stability, but not enough to balance a vee hull on the apex of the vee.

The force that causes a vee hull to ride level is the chine flat and immersion up to that point. So long as a sufficient amount of the hull remains in the water up to the chine, the hull will run reasonably level. But now that boats are being made so light with the use of foam cores replacing heavy fiberglass, at higher speeds these hulls are rising high up too high out of the water. In many cases, I've observed the chines on both sides becoming completely exposed at even moderate speeds. On some boats, the chines are exposed even while at rest.

Then there's a difference between outboards and inboard powered boats. Outboard are far more sensitive to chine riding because the weight of the engines is on the stern, and because outboards weigh less than half of gas inboard engines, and five to six times less than diesel engines. Add to this the fact that outboard boats themselves are generally lighter and much faster, and it becomes easy to understand why chine riding has become a major problem for outboard boats. Which is not say that it doesn't happen with convertible sport fishermen, because it does as these boats get lighter and go faster.

Of course, it's one thing to go listing along at 20 degrees in an open outboard, something else again when you're sitting way up on a flying bridge, in which case chine riding becomes an intolerable problem.

I've been complaining for years that it's a mistake for builders to strive for lighter and lighter boats. I've pointed out that when a boat gets too light, it adversely affects its moment of inertia to the point where wave induced motion becomes too rapid and violent. As I peruse the discussion forums on the Internet, I see more and more comments about vee hulls rolling too much. This is wrong; what fishermen complain about as boats rolling too much is not really rolling moment, but period of roll. The fact of the matter is that heavier boats may roll more, but they also roll slower, which is a more pleasant motion than the rapid whip-snap rolling motion of a very light boat that throws people off their feet.

You can understand this because you know that it takes far more energy to start a heavy object moving than for a lighter object. And, it takes more energy to stop its movement. Thus, the heavier boat rolls move, but does so more slowly, whereas the light boat can have its motion start and stop rapidly.

The same problem that is causing this is related to chine riding.

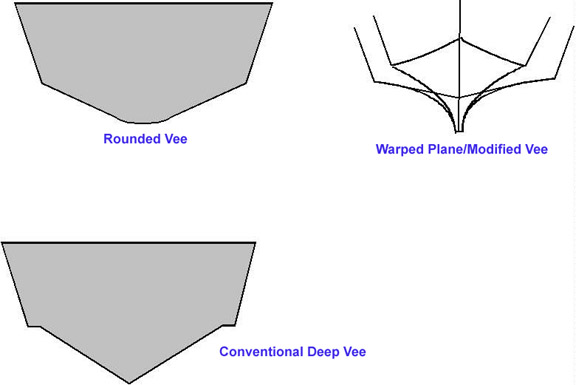

Now that we're back with our fuel price problems a la the 1970's again, fuel economy is again becoming a major issue. Unfortunately, this will provide even more motivation to make boats still lighter yet. If this is what is necessary to be able to make boats affordable, then what designers need to do is to change hull shapes. The deep vee will no longer be a viable option. Instead, we need to go back to the future, back to the days of the warped plane hull that prevailed from the 1930's through the 1950's, illustrated in the drawing above.

In case you're not familiar with this shape, it is still commonly found in the New England work boat hulls and some pleasure boats with similar lines. The warped plane typically has a very deep entry that begins to flatten out back aft to the point where there is very little angle at the stern. Thus, it has a knife-like edge meeting the waves and a flat stern section that provides a good running surface as well as good stability. This shape is very efficient, so much so that only one engine is usually needed compared to the twin engines needed to drive vee hulls. This shape will not solve the problems of excessively rapid motion caused by ultra lightness, but it will eliminate the stability problems associated with deep vee hulls.

The down side of the warped plane hull is that beyond a certain speed it has a tendency to pound as the running surface is shifted further aft the faster it goes. The bottom line is that if you want to go really fast, there is always a big price to pay. There's no such thing as a perfect hull shape, and each has its strengths and weaknesses.

If good rough water performance means anything to you, then you need to pay attention to this before you buy. No one should ever buy a boat without taking it for a test ride. I suspect that the primary reason why I've surveyed so many badly performing CC boats is because the owners simply couldn't stand them anymore and decided to dump the problem on someone else.

So check it out carefully before you buy and don't end up finding out the hard way that you're the proud owner of a chine rider.

Other Modified Vee Shapes

Recently, I received a phone call from a guy who had purchased a new CC boat, and was very unhappy with it. "I couldn't believe that a boat that costs so much could have such a lousy ride," the fellow said. "This boat beats your brains out in a two-foot chop," he complained. "And not only that, but it chine rides."

Since I was familiar with the hull shape this builder normally used, I asked him if his boat had a rounded vee hull. "Yep," he replied. "It looks like a really deep hull, so why does it pound so much," he asked?

A rounded vee hull shape is illustrated at upper left of the above drawing. This type, instead of having the bottom panels coming to a point on the bottom, the keel area is heavily rounded. This provides a great deal of extra lift, but utterly defeats the purpose of a vee hull. Instead of a vee parting the water, here we have a flattish rounded surface that presents a lot of surface area to facilitate slamming.

Dealers will often talk about dead rise angles, but generally speaking, dead rise angle means little unless we're talking about a constant dead rise boat. Constant dead rise means that the hull is the same vee angle along its entire length. Very few builders use that shape, instead choosing to modify the vee shape somewhat by making it a bit deeper in the bow than at the stern, which is the case with the vast majority of boats.

What counts most is the vee angle at approximately amidships because, when running along at speed, a good portion of the bow remains out of the water, so that the slamming area is centered from amidships, on aft. You can have a good performing boat that has only 18 degrees of angle (per side), that will give the impression of a very shallow bottom. At the amidships location, that angle could easily be 30 degrees; thus this would be a misperception if one relied solely on the angle at the stern.

You can get a better understanding of how this works out by imagining a rectangular sheet of cardboard, and holding one end in each hand, imagine twisting each end in opposite directions. That is the essence of the modified vee, so that the range of change of the angles is nearly infinite. Somewhere in that range of change is going to be the optimal shape. You can create a bow angle that is very steep and a stern section angle that is totally flat, or also very steep.

The steeper the angle all around, the less efficient the hull will be. That is because a vee angle creates more wetted surface, and therefore more drag. It will take more power to drive it at equivalent speeds, and therefore more fuel. This is one reason few builders use the constant dead rise vee anymore. Another is that the constant vee angles do not create hull shapes that provide the optimal interior volumes.

Ultimately, you have to decide for yourself which qualities you are willing to sacrifice.

Originally posted June 2, 2001

David Pascoe is a second generation marine surveyor in his family who began his surveying career at age 16 as an apprentice in 1965 as the era of wooden boats was drawing to a close.

Certified by the National Association of Marine Surveyors in 1972, he has conducted over 5,000 pre purchase surveys in addition to having conducted hundreds of boating accident investigations, including fires, sinkings, hull failures and machinery failure analysis.

Over forty years of knowledge and experience are brought to bear in following books. David Pascoe is the author of:

In addition to readers in the United States, boaters and boat industry professionals worldwide from nearly 80 countries have purchased David Pascoe's books, since introduction of his first book in 2001.

In 2012, David Pascoe has retired from marine surveying business at age 65.

On November 23rd, 2018, David Pascoe has passed away at age 71.

Biography - Long version