Navigation Lights

by David Pascoe

You don't want to read this, and I don't want to write it. The subject of navigation lights is boring, but if you read this, it just might save your life. In fact, I've been putting it off for several years until I heard about a grizzly accident on Lake Erie in which three people were killed when two small boats collided. That was one of just many deaths and maimings that have occurred with nighttime collisions this year, all because of defective lights.

Take Lighting Seriously

I take lighting seriously, and I'll tell you why. I've run boats all over the western hemisphere, and not once have I ever run aground or hit anything. Yet on at least three occasions that I can remember, I nearly had night time collisions. Once with an oil tanker, no less. If you don't think oil tankers move fast, try misjudging your bearings and closure rate sometime, and you'll discover the hard way that they really can move 25-30 knots.

It's hard to appreciate how flat out dangerous nighttime running is until you have one of these close calls, or worse, you end up like the three people on Lake Erie. They probably never had a close call, so that was their first and last chance to get it right. Even when all boats have proper lighting, it's very difficult to judge bearings and closure rates. I'll say it again, operating a boat at night is dangerous, and it requires the utmost in attention and knowledge to do so safely. But when boats have improper lighting . . . well, you don't really have a chance of avoiding an accident.

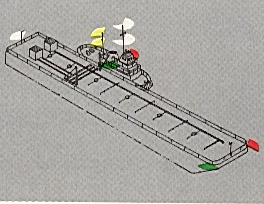

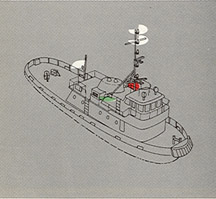

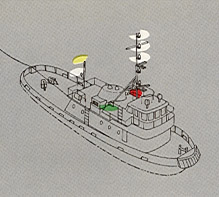

Could you identify these vessels by their lights? These are three of the most dangerous light combinations you could face.

- Tug pushing barge alongside

- Tug pushing barge astern

- Tug towing a barge

Lighting Defects

The simple fact is that at least 1/3 of all boats that I survey have lighting defects. That's right, one third. That's a pretty good reason why there are so many accidents. No?

1.

The most common reason is that something has been installed in front of the light which blocks it. Radar scanners, dinghy's, searchlights, you name it. If the builder did install proper lights on the boat, people will do something that interferes with the light. Mainly because they just aren't aware of what they're doing.

2.

The second most common problem is that the lights weren't installed right in the first place, or the builder installed something that obscured the light.

3.

The third most common problem is that the lights are so puny, such cheap-ass crappy pieces of junk that one might just as well rip them off and throw them overboard for all the good they do. Some of the lights I see must have a grand total production cost of 59 cents in Malaysia. But some nut paid $40 for the dang thing. They're that bad. Others are so poorly designed that they won't keep water out in a 30 second rain shower, so the thing corrodes and craps out.

4.

The fourth most common problem is the people never check their lights to see that they work.

5.

The fifth most common problem is that the installation of the lights did not take into account the running angle of the boat. Since all boats do not run at the same angle, it often happens that the attitude of the boat dramatically changes the angle at which the light can be seen. The bow may be pointing so high that the lights can only be seen by aircraft. A boat far away may be able to see it, but one close-on can't.

Important Things to Realize

There are several important things boaters need to realize.

It's hard enough to operate by night with good lights, but to run around with marginal lights is to flirt with catastrophe. Maybe you can see where you're going, but the other guy can't see you.

Night vision can be highly illusory. Anyone who's spent some time out on the water at night knows how hard it is to judge distances, and how easy it is to be fooled by optical illusions. It is especially difficult in an environment with a lot of lights, such as near a city. Picking out the lights of a moving vessel from a background of dozens or even hundreds of lights is very difficult, if not even impossible. Vessels with poor or defective lights likely go unseen.

Many people have very poor night vision, or lack the kind of visual perception that is needed to operate safely at night. This kind of visual perception is a skill, not merely a matter of good vision. It's the ability to quickly pick out lights and identify their nature. Whether unskilled or poor vision, it doesn't help matters if your lights are not up to snuff.

Many people who operate boats at night quite simply don't know what they're doing. Ask them a question about taking a bearing of an oncoming boat based on the display of lights, and about 95% of all boat owners would give you a dumb look. That's because they have no training whatsoever. Keep that in mind, because that's what you're up against when running at night.

Check your lights.

-

Make sure that the lights meet Federal Regulations, and that they are not obstructed by anything.

-

Check to be sure that the running angle of your boat doesn't obscure visibility. Does the stern on the transom sink so low that the light is hidden by the wake, and can't be seen by anyone but you? Over-runnings have occurred because of this -- are actually quite common in South Florida.

-

Check the intensity: Do they look weak or dim? Is it a cheap light, is it too small, or do you have the wrong kind of bulb in it. Your red and green lights should be shining brightly, not a dull red or green. Can they really be seen a mile away.

-

Make sure that your 225 degree white light isn't blinding YOU. This is a very common problem on small boats and flying bridge boats where there is no good place to mount the light.. The builder mounts the light right in front of you so that it hinders your vision. That's the builder's fault and you should call him to task on it.

-

If you have a small boat that has the minimal lighting options allowed (such as combination lights, and those flimsily little things mounted on aluminum sticks that don't work most of the time, change them out to good lights.

-

Small boat owners should be more appreciative of the fact that small boats are much harder to see from larger vessels. That's one reason why the highest proportion of collisions involve small boats. Small boats need better, not lesser lighting as the rules allow.

Check you knowledge of night running.

-

Do you know how to take bearings? Do you know what your looking at when facing a ship, a tug, or other types of vessels?

-

What do you do when facing a shoreline dotted with hundreds of different color lights?

-

Do you allow yourself to be distracted by onboard guests when operating under these difficult conditions?

-

Do you post a second lookout? Have you ever?

-

Do you operate defensively, instead of assuming that the other guy is also looking out for you? Chances are he isn't.

-

Do you occasionally look behind or beside you, instead of assuming that all hazards are ahead? Nearly half of all collisions involve running down, meaning hit from behind.

-

Do you maintain high speeds even when there are a lot of unidentified lights around you? Does your speed exceed the amount of time you have to identify what's around you? If so, you're going too fast.

- Do you know how to judge closure rates at various angles?

If you answered no to any of the above questions, you need to brush up on your nighttime operating skills.

Story time

One night I was on my way to the Exuma Cays, Bahamas. It was late and there was a full moon out, which actually made visibility more difficult. As I was crossing a shallow section of the Bahama Banks, I was checking my coordinates on the chart very closely. There was a rather narrow slot in the shallow bank that I had to hit dead-on, so my nose was down on the chart and the SatNav most of the time. I thought I had the ocean to myself as I had seen few other lights all evening.

Convinced I was on course, I flipped on the autopilot, and was leaning out the pilothouse window watching the phosphorescence of the water go by. Looking down into the dark water, suddenly that inky black water becomes illuminated by a lighter blue glow from below. What in God's name is that, I wondered? Anyone who's spent a lot of time at sea knows that strange things can happen. What's behind all those crazy stories of the Bermuda Triangle are the illusory tricks the sea can play on our eyes by day or night. I look up at the moon, then back down at the water. And here I am looking down at this eerie blue/white glow from the bottom of the ocean.

Holy Mackerel!!! It dawns on me; it's the damn moon light reflecting off the white sandy bottom. It never occurred to me that in this very clear water that could happen. We're heading into the reefs and I'm in big trouble. Yike, now I can pick out coral heads on the bottom. Hitting the autopilot switch so hard it breaks off, I leap for the wheel and swing it around hard -- to my horror straight into the path of an overtaking fishing boat charging along at around 30 knots.

I see him when my vessel is nearly perpendicular to his. Spinning the wheel around to the opposite direction, without ever touching the throttles, I can hear lamps, television sets and dishes crashing below as the yacht heels over wildly.

Fortunately, that operator wasn't daydreaming as I was, and saw me start my turn as soon as it was initiated. He turned shortly after I did. The two vessels were less than 50 yards abreast, with him slightly behind. Sure, I could blame him for following too close, but in my panic I didn't look before initiating a hard turn. Who would have been at fault? Both of us, actually. Me for not looking and him for overtaking too close abeam with no signal, and no reason to be that close.

As it turned out, we weren't in as shallow water as it appeared, about 30 feet. Never before had I seen moon light reflecting off a white sand bottom so brightly, but there it was. We were oncourse and all was well with the world when illusion and circumstance conspired against me. Fortunately, the 60 foot yacht I was piloting had big, bright lights. You know, those five inch jobs that far and away exceed minimum requirements.

So there you have it, in the middle of an apparently empty sea, two lone vessels somehow manage to come together almost in collision. Needless to say, that cured me from any further assumptions of the ocean being empty. Spend enough time out there and you get the idea that there is some sort of magnetic attraction between boats that somehow pulls them together. It's not the boats, of course, but the unconscious human tendency to steer toward other boats, no matter how empty (or perhaps because of the emptiness) the space around them. That old saw about two ships in the night; this is where it came from.

I'll spare you any further sea stories, but that is just one of many such incidents involving illusions and lights. In this case, good lights saved my skin, whereas if the yacht had weak lights, the other guy might not have noticed my turn in time.

Posted December 20, 1998

Visit davidpascoe.com for his power boat books

Visit davidpascoe.com for his power boat books

David Pascoe is a second generation marine surveyor in his family who began his surveying career at age 16 as an apprentice in 1965 as the era of wooden boats was drawing to a close.

Certified by the National Association of Marine Surveyors in 1972, he has conducted over 5,000 pre purchase surveys in addition to having conducted hundreds of boating accident investigations, including fires, sinkings, hull failures and machinery failure analysis.

Over forty years of knowledge and experience are brought to bear in following books. David Pascoe is the author of:

In addition to readers in the United States, boaters and boat industry professionals worldwide from nearly 80 countries have purchased David Pascoe's books, since introduction of his first book in 2001.

In 2012, David Pascoe has retired from marine surveying business at age 65.

On November 23rd, 2018, David Pascoe has passed away at age 71.

Biography - Long version