Safe Harbor

Lessons learned from recent hurricanes can help boaters in Southeast Florida protect their boats against the ravages of these devastating storms.

by David Pascoe

We have been in a "quiet" period, but the current pattern seems to indicate a very active cycle. That's good reason for boat owners to give special attention to this year's hurricane season. (- Posted spring 1996.)

It is said that black clouds sometimes have silver linings. If there is any lining at all, yet alone a silver one, in the last three hurricanes that have struck Florida, it is that we have learned that there is much more that boat owners can do to protect their vessels than was previously believed.

This doesn't have to happen to your boat. With narrow slips and entirely inadequate pilings, the boats in this marina never had a chance. Numerous cleats and pilings lagged into the concrete docks came loose.

The contrast between the effects of Opal that struck the Panhandle and Andrew that hit south Dade County is striking. One thing we've learned from these storms is that the central and southeast coast offers much greater protection than other areas of the state such as the west coast and panhandle. Another is that good preparation and choosing the right location for storm shelter can substantially reduce storm damage. In addition, fully half of all those boats that were severely damaged or destroyed were the result of owners who took inadequate, or no protective measures at all. Those boats that suffered the least damage were not just lucky; they had owners who were most knowledgeable about hurricanes and made the best preparations. My study of the last four storms, especially Andrew, indicates that overall boat loss and damage could easily be reduced by as much as 50% if boat owners were better educated about how to protect their boats. The information in this article is based on a 4 year study involving nearly a thousand boats. I'll review many of the things that were learned, plus give some new tips on what you can do to minimize loss and damage.

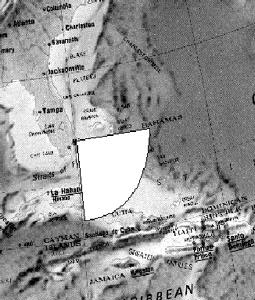

The normal hurricane approach zone to South Florida extends from east to south. This is the danger zone for boats. Notice that the most dangerous winds will tend to be from an easterly direction regardless of the direction of approach.

Moorings Versus Docks

My estimate of the survival rate of boats at anchor in the last four storms is between 5-10%, depending on location. That really says it all as far as anchoring is concerned. There are simply too many unknown factors involved for mooring to be reliable, and there's a long list of reasons why. The use of anchors for secondary holding, or to keep boats away from docks is fine, but dependence on anchors almost invariably fails. Certainly there are exceptions to this, but unless you have a great deal of certainty about the holding ground and other conditions, anchoring is a poor option.

My recommendation is that anchorage should be avoided whenever possible. It's better to put a boat up in the mangroves rather than taking a chance that it will end up against a concrete dock, sea wall or rocky shoreline.

Boats Ashore

Beware that boats ashore do not fare well because they're up high and offer too much wind resistance. They stand about a 90% chance of being blown over. Sailboats stand no chance of remaining upright.

Trailer Boats

By far, the best option for trailer boats is to get them off the trailer and on the ground with the bow facing east. Otherwise, the wind will get under the hull and lift it right off, usually flipping it over. On average, powerful, fast-moving storms only dump about 5-6" of rain so you can put some water in the hull to weight it down without worrying too much that it will fill up. In any case, fresh water damage is better than it being blown around.

This illustration shows the hurricane direction wind zones relative to the eye. By understanding wind directions relative to storm direction, knowing where your boat will be relative to the storm helps determine the direction of hurricane force winds that it will be subject to, as well as how much storm surge to expect.

Wind Direction

The geography of southeast Florida provides certain advantages for boat owners. One is that the most dangerous storms approach from the east to south quadrant. Storms approaching from any other direction will not have the same devastating effect because there will be no storm surge. Another is that the proximity of the Bahama Banks and the narrowness of the Gulf Stream has served to limit storm surges to considerably lower than what is predicted. However, this protection factor decreases somewhat in proportion to the intensity of the storm.

Relative to the eye, there are three major wind zones in a hurricane, north, center and south. The north zone will experience winds mainly from the east. In the central zone, the eye, the winds can be from all directions. In the south, the worst winds will be westerly, causing a low, rather than high water problem. The north zone of a hurricane usually has winds of longest duration.

Use the National Hurricane Center's strike probability estimates to estimate which side of the storm you're likely to be on. This will give you a better idea what to expect, and be better able to prepare. If you're on the south side, you don't have to worry about storm surge, but the opposite effect, low water. Most boats wrecked on the south side of the storm resulted from cleats pulling out and lines parting because there was insufficient slack to allow for extreme low water. If the storms course is fairly constant, you can prepare for this. If not, the best you can do is attempt to choose a happy medium.

Remember that the water level difference from extreme highs and lows can easily be 20' and you can't prepare for both. If you prepare for high water and end up on the south side, your best efforts will be defeated. However, if you live close to your boat, you may get a 6-8 hour window of opportunity to make adjustments. If your boat will be on the north side, it will usually become fairly obvious with adequate time to prepare for extreme high water.

The domino effect occurs when one boat on a canal breaks loose and crashes into others, resulting in a chain reaction that ends up with boats piled up at the end of the canal.

Cross-tying

The majority of boats in south Florida are docked on the hundreds of miles of man-made canals. In years past, cross-tying was illegal, but that law has since been repealed and many people now take advantage of it.

Tying your boat fully across a canal has advantages only under certain circumstances. First, one can't do it too early because you block access for other boats. People who've tied across canals 36 hours in advance have been known to have their lines cut by their angry neighbors. Be considerate: the generally accepted practice is not to cross-tie more than 12 hours in advance. Be neighborly and consult with other residents on your canal and make sure that at least a half-dozen neighbors have your name and phone number so that they can reach you, especially if you're not a homeowner on that canal.

Another disadvantage is that tying across certain canals is vulnerable to what we call the domino effect. In south Florida, it is mainly the east-west canals that are most vulnerable because that's the usual direction of wind and storm surge. On the other hand, north-south canals will be closer to perpendicular to the wind and waves, and therefore have better much protection, and are much less vulnerable to the domino effect.

The domino effect occurs when boats at the head (windward) of the canal break loose and are driven downwind, crashing into all the other boats that are cross-tied. In the aftermath of Andrew, hundreds upon hundreds of boats on east-west canals were found piled up at the end of canals, most of which were cross-tied. Those on north-south canals did not suffer this fate.

Therefore, when contemplating whether to cross-tie, consider whether the yacht will be vulnerable to the domino effect. Boats at the west end of the canal are far more vulnerable than those near the head (east end) of the canal. If possible, try to check on the mooring of the boats upwind of you. If someone's done a lousy job, or has tied to weak or rotten docks, then chances are that his boat is going to wreck yours. You'll probably stand a better chance if you can use anchors to stand off from the dock, or find a better location, rather than being a sitting duck at the end of the canal. If you can generate a neighborhood team effort, so much the better. Get all the boat owners involved and insure that all boats are well secured. The point is, beware of the dangers from upwind.

With slip clearance of only two feet, there was no way to protect this yacht from battering against the pilings.

Docks & Pilings

Low dock pilings are one of the biggest destroyers of boats during a hurricane because of storm surge lifting the boats above the pilings which then puncture the bottom or hull sides. If the boat is going to stay at the dock, one of the most important considerations is to be sure that the dock has tall pilings. An adequate piling height is six feet above the gunwale. Much higher than this is not practical, but if the pilings are only a few feet higher than the gunwale at high tide, then one way or another the boat has to be gotten away from the dock. Narrow slips are another problem. If a dock slip is too narrow, then there's no chance of keeping it off the pilings with the rise and fall of storm surge. The boat is likely to be battered by its neighbors. Boats docked in tightly packed marinas, even if well-sheltered, need to be moved to better locations. If the boat can't be moored away from the pilings, count on it being destroyed.

The Coco Plum Experience

This private marina at the south end of Coral Gables gave us an excellent lesson in hurricane protection in the aftermath of Andrew. Most of the boats in all the marinas to the north and south of Coco Plum were destroyed, even though all these marinas directly front Biscayne Bay. And yet, incredibly, not one boat at Coco Plum was lost, and only a few had significant damage.

So what distinguished this marina from all others? First, the entrance channel to the marina has a sharp dog leg that greatly reduced wave action. Next, the marina was protected by a buffer zone of dense mangroves. But just as important, the concrete docks at the marina have very wide slips with heavy, tall pilings. This allowed boat owners to tie their boats well off the docks. Even with a 10' storm surge, not one boat came down on the pilings, and hence none were lost. Whereas at Diner Key, Matheson Hammock and Black Point, nearly all the boats were lost because all had narrow slips and inadequate pilings. The lesson for boat owners with boats in narrow slips is that your chance for survival is very slim indeed.

Marinas

It's no longer legal for marina owners to force boat owners to leave in the event of a storm. However, many of the marinas on the east coast are quite vulnerable. Consider these points to determine whether to remain in a marina. (1) Slip width should be minimum 140% of the beam of your boat. If your boat can't rise and fall 10' without coming down on a piling, you need to move. (2) Piling height should be 6' above highest gunwale point. (3) Check tidal zone of pilings; ideally there should be no wastage. (5) If the marina has lumber bolted to concrete instead of full-size, driven pilings, move. (6) Try to make sure that the boat is tied facing into the wind of the approaching storm, an easterly direction. (7) If your neighbor's boat is not as well tied as yours, his boat will likely wreck yours. (8) None of the marinas on the barrier islands, or fronting the bays, are secure. Move your boat or lose it.

Choosing Another Location

All throughout south Florida there are lots of good refuges available. It just takes a little time seeking them out. Consider finding a well-protected, inland canal with a good dock. Don't bother with anything with substandard pilings. Important considerations are how far inland you wish to go, and the obstacles of getting there. Check when bridges will be closed and locked down. New River traffic, for example, is organized into "armadas," with certain specified periods for upriver travel. Moving upriver can be a very time-consuming job. Be sure you're prepared to meet the schedules. Plan your move well in advance.

The pilings for the Bertram in background are too close and too low. The sailboat in foreground didn't have any pilings at all, just a few pieces of wood lagged to the sea wall. Good pilings would have prevented this.

Canal Docks

Canals that are well away from the Intracoastal offer some of the best protection, so long as it has good pilings. Fig. 4 shows what usually happens if the pilings are not well suited to the boat. The best arrangement is to have one piling each, fore and aft on the water side so that the boat sets between the dock and outer pilings. However, if there is not adequate clearance, they'll probably do more harm than good. Pilings like this will not only tend to fend off break away boats, but help keep you off the dock without having to cross-tie on a canal. If you're a homeowner and your canal is wide enough, it costs about $2,000 with permits to drive two wood pilings, and its well worth the cost.

Never tie to wooden docks, especially cleats attached to docks; they're guaranteed to come loose. After hurricane Opal, virtually every wooden dock we saw was damaged or destroyed and many pilings were pulled out. You have almost no chance of survival tied to a wooden dock. Moreover, pilings that are jetted in with water jets, instead of being driven, have very little holding power. If you're using cleats on concrete sea walls, make sure they're well attached. The bases on Coconut and Royal Palm trees make good mooring posts in winds up to 150 MPH. Beyond this, even the palms start coming down. But make sure the palm is not too close to the water's edge.

Knots and Lines

Making the proper attachment to a cleat or a piling is far more important than one might imagine. What's okay for normal use often fails during the violence of a hurricane. You should have an extra set of new, and slightly oversized storm lines - about 1/4" larger than normal size. By all means, do not depend on aged cordage. Remember that, although an older line may look okay, it may be seriously weakened by ultraviolet or fungicidal degradation that may not be visible. Use new lines for primaries and the normal dock lines as backups or doubles.

When doubling up lines, try to reduce dependency on a particular tie up point. Any time you can double a line to a different point, do it. Two lines tied to one piling or cleat are of no help if the piling or cleat fails. Spread lines to as many different tie points as possible. Consider that under high water conditions, your lines will be angling downward as the water level rises.

Never tie to cleats on pilings. Lines tied to pilings should have a fair lead off the curve of the piling (tangential) and should not be cinched by the knot so that the line is pinched or pulled by the knot. Take only two wraps around the piling, making sure that they do not overlap. Cinch knots or hitches around the piling should not be used as this pinches the rope. Remember that it is the friction of the line around the piling that provides 98% of the holding power. There will be very little pressure on the knot which merely keeps the line from slipping. Do not use bowlines; instead, three simple half-hitches around the standing end are more than adequate and will minimize chafing. Then wrap the free end back around the piling with hitches to keep it in place.

Cleats, Chocks and Pulpits

There is a right way and a wrong way to attach a line to a cleat. Cleats can be troublesome because rope can get pinched and abraded if not tied right. We recommend that only lines with properly made eye splices be attached to cleats. Put the eye through the center hole of the cleat and fold it over. If you have to use hitches, make sure the line leads off the base as fair as possible with minimal potential for chaffing against the hitches.

The rule for cleats is, the larger the better; the smaller the cleat, the more it pinches. Nowadays, mooring cleats seem to be getting smaller and more poorly installed. Now is the time to take a look at how they're attached. Do they have adequate back up plates on the under side? Aluminum or fiberglass blanks make for the best back up plates. Plywood doublers will crush and allow the cleat go loose. Back up plates should be as large as practical, preferably 1.5X the length of the cleat and 1X length wide. If your bow cleats are too small, and don't have adequate back ups, seriously consider replacing them.

Our studies of Hurricane Opal revealed that large numbers of boats broke loose from anchorages and docks because of lines cutting on various areas of bow pulpits. A lot of pulpits have a sharp edges on the underside that can very quickly slice through a line. The motion of a boat in a storm is far more violent than one might imagine. A pitching pulpit can snag a dock line or anchor rode. If the bottom edges of your pulpit are sharp, its a good idea to have the edges rounded over as much as possible.

For chafe protection, we recommend that stiff plastic hose, such as old garden hose, be slid over the end of the line. Plastic hose is slippery and resists abrasion better. The hose should not be slit down the middle because the chances of it coming off are very high. Drill a hole in each end of the hose and tie it to the mooring lines with nylon string, running the string through the laid line to prevent movement. Don't use rags for chafe protection, they won't do the job.

Mooring chocks tend to be particularly troublesome because they're usually poorly designed, tending more to damage the line than protect it. There are several types of mooring chocks that are extremely bad this way, having sharp corners. If your chocks are like this, get them replaced and make sure that they have good back up plates below. Many are just screwed on and won't hold. Through bolting into an aluminum back up plate is best. Its better not use a chock than one that's guaranteed to cut the line.

Sailboats in particular have notoriously small, badly shaped and poorly placed cleats and chocks. They are often placed in a cluttered spot on the bow with other equipment that will cut the lines. This is one of the reasons why so many sail boats break loose. If this describes your boat, consider upgrading if you want your boat to survive a hurricane.

Tophamper

Anything that increases the windage above the superstructure is called tophamper. Virtually all canvass, tops and sails and enclosures should be removed from the vessel. If you can get these off the boat completely, so much the better. Cabins stuffed full of sails and canvass have hampered many a salvage operation. Outriggers should be removed from the boat, as well as antennas, particularly if they're on a tower. Don't hesitate to cut antenna wires, if necessary, to get them off. For sailboats with a lot of external halyards, we recommend that you cut the end and pull them down; they dramatically increase wind resistance aloft. It's also a good idea to remove the boom, if you can, and lash it down ashore.

Check all pedestal seats to be sure that they are securely locked. All exterior cushions, even if secured with snaps, should be removed and stored inside. For loose deck furniture, if you can't remove it, group it together in a corner and thoroughly lash it to railings. Tape up all exposed cabinets and drawers. If you have a Plexiglas bridge windscreen, unscrew it and store it below.

These boats survived the eye of Andrew, despite fronting directly on Biscayne Bay with a 10' storm surge, by a combination of cross-tying and anchors. The sail boat had 3 anchors out that saved it when the forward mooring lines broke.

Tuna Towers

A number of sport fishermen with tuna or marlin towers were literally capsized by wind. When the vessel starts to heel over, the Bimini or tower top then starts to catch the wind. Once this happens, it will either capsize or be torn away from the moorings. If a strong category two or higher storm is approaching, we recommend that a Bimini strung on a tower be removed since it won't survive anyway. This will greatly reduce the chance of capsizing. Remove everything that will be wind or water damaged.

Engine Protection

Some yachts sank because the boats heeled over so far that the hull side ventilators went underwater. But also remember that 150 MPH winds eliminate any distinction between sea and sky. Wind-driven water is going to go right into the engine room vents. If the engine room hull side vents are small enough, they can be taped up with duct tape. If the vent is larger, use a thin piece of plywood and screw it directly into the vent cowl or even the hull side if that's all that is available, and then tape over the edges.

Don't forget that on the reverse side of the storm, the boat may be hit by winds from astern. If you don't want to take the chance of water being driven up the exhaust and into your engines, then plugging the pipes is the thing to do. Sailboats and gas engine boats can use simple wood plugs. Sail boat owners absolutely should plug their exhaust lines and close the sea water intake sea cocks. For larger diesel exhausts, the inflatable balls available at most marine stores are the best solution.

If you have a generator under an open cockpit deck, cover it with sheet plastic so it won't get wet. Close the water intake sea cock. If you have the proper size bungs, stop up the exhaust outlet. Tape over with duct tape the fuel and water tank vents on the side of the hull.

Electronics

It should go without saying that all external electronics should be removed. That includes those mounted in covered boxes. After Andrew, we found shredded leaves inside closed, locked electronics boxes. The wind force was so great that it bent the plastic doors, creating gaps. Again, don't hesitate to cut wires and cables for removal. The cost of reinstallation is far less than having to replace costly electronics. If electronics inside boxes cannot be removed, completely tape around the cabinet doors with duct tape to help keep water out. Tape tightly over all instrument faces that can't be removed, as well as switches and the like.

Windows & Hatches

One of the more amazing results of our survey was how well window glass holds up even in the most extreme winds. Less than 5% of all boats we looked at had broken window glass. Plexiglas, on the other hand, fared poorly. However, wind-driven rain is a serious problem that can find its way into the smallest cracks. We also learned that most superstructures on motor yachts are fairly weak. That means that wind stress often distorts superstructures enough open up small gaps in window frames and between glass panels. Also that the wind can set up some really heavy vibration that will rattle sliding glass panels open. Be aware that wind pressures can literally bow window glass and hatches, opening up gaps that you'd never imagine possible. We've found shredded leaves inside boats and couldn't imagine how it got there. We recommend that all windows be locked and taped with duct tape. Tape all joints and seams on both sliding and fixed window glass on the outside. If you have window covers, leave them in place; they often help. Also tape around all hatch covers and entrance doors.

Securing the Interior

We already mentioned how violent the motion of the boat can get, so it's wise to take the same precautions on the interior. For example, in the galley clear out all elevated cabinets where doors will open and contents spill out. Even tape probably won't hold the doors shut. Put breakables in boxes down low. Remove all heavy objects that will force doors open during extreme rolling. Anything loose like televisions, bric-a-brac, lamps and the like should be secured on the sole. Prepare for some serious water leaks. Slide furniture away from windows. Raise venetian blinds and take down drapes; they'll get wet for sure and if a window breaks, they'll cause even more damage. Take up all carpets in lower quarters and place on berths. Roll back or take up carpet in way of exterior doors, then duct tape the door jambs when leaving the boat to keep wind driven water out.

Mattresses on berths in forward cabins in way of port holes and hatches should be wedged up on end so that leaking won't soak them. Strip, pillows, sheets and spreads and store in a safer place.

Don't forget the refrigerator. Clean out all perishables and glass bottles that will slide around and break. Make sure the door is firmly latched. If you have an AC/DC reefer, make sure that is turned OFF so that it won't drain the batteries.

Find the sea cocks for the heads and close them. Close or plug all sink drains. Shut off all other sea cocks except for the main engines.

Disconnect and stow shore power cords away. Electrical power will be lost anyway and leaving it plugged in will only result in the loss of the cord. Turn off all DC circuit breakers except the main and bilge pumps. Then make sure that all pumps are working and the batteries are fully charged.

Sail Boats:

Owners often strip off all sails and canvass and stuff it all down below. Unfortunately, if a boat fills partly up with water, this creates a terrible problem getting these materials out of a flooded cabin. If you can, get all loose sails off the boat. If you take the furling genoa down, again, don't stuff it in the cabin. Tie it to a tree or something, or take it home. The cabin areas should be kept as free as possible to tend to an emergency if necessary.

Imagine hosing down the interior of your boat and then letting it sit for a couple days. That's what the inside of your boat is likely to look like when you finally get to it, many days later. Your boat will leak in ways you never imagined impossible. All that stuff packed into lockers needs to be removed. The easiest way to deal with it is to stow it all in heavy trash bags and seal the ends tight. Then stow them tightly in a high corner somewhere.

Remove vent cowls and heavily tape over the openings.

Take all the bunk and dinette cushions, stand them edgewise and wedge them in place such as around the dinette or a quarter berth.

Close all sink and head sea cocks. Check to be sure that cockpit scuppers are clear. Loch the wheel or lash tiller in the centered position, not to one side. The Bimini top should be removed from the boat, frame and all. Don't try to lash it down because the wind will tear it free. Lash it down ashore. Remove all equipment attached to the lifelines or pulpits.

Duct tape over all windows, ports and hatches around the base. When leaving the boat, tape over the companionway hatch joints.

Express Cruisers

If you have an open cockpit express cruiser, take down the top frame because you'll lose it anyway; if the frame gets loose, it will do great damage. Dismantle the top, remove the cover, and stow the frame on the cockpit deck. If you have a canvass instrument cover, it won't help. Instead cover instruments and switches with duct tape, applying in a shingling fashion. Just remember to get it off soon after the storm. Remove electronics and tape up any open holes in the dash. Tape all switches and the ends of the cable connectors. If you have a generator, cover it with plastic. Next, duct tape the gaps of all hatches in the cockpit deck. This will help prevent water from getting in the engines, particularly the generator. Then, make sure the deck scuppers are clear. Tightly lash fixed, folding swim ladders. Remove all antennas, don't just fold them down. If there are electric panels in the cockpit, tape around the doors. Remove all loose deck equipment such as fender racks, life rafts and anchors. Before leaving the boat, tape over the companionway door jamb. If you have a gas boat, we recommend that you shut off the fuel valves to all engines, especially the valve at the tanks.

See also Hurricane Season 1999

Related Reading:

About the Author: Dave Pascoe is a Ft. Lauderdale, NAMS Certified Marine Surveyor with 30 years experience in dealing with marine catastrophes, starting with Hurricane Agnes in 1968. Most recently he has worked Hurricanes Andrew, Erin, Opal, Hugo and Marilyn. The information contained in this article is the result of his studies of the effects of these storms on boats of all types, and in a variety of geographic locations. (He currently resides in Destin, Florida. Retired in 2012 from marine surveying business.)

First posted in spring

1996 at marinesurvey.com.

Copyright 1996 - 2014 D.H. Pascoe & Co., Inc.

Visit davidpascoe.com for his power boat books

Visit davidpascoe.com for his power boat books David Pascoe - Biography

David Pascoe is a second generation marine surveyor in his family who began his surveying career at age 16 as an apprentice in 1965 as the era of wooden boats was drawing to a close.

Certified by the National Association of Marine Surveyors in 1972, he has conducted over 5,000 pre purchase surveys in addition to having conducted hundreds of boating accident investigations, including fires, sinkings, hull failures and machinery failure analysis.

Over forty years of knowledge and experience are brought to bear in following books. David Pascoe is the author of:

- "Mid Size Power Boats" (2003)

- "Buyers’ Guide to Outboard Boats" (2002)

- "Surveying Fiberglass Power Boats" (2001, 2nd Edition - 2005)

- "Marine Investigations" (2004).

In addition to readers in the United States, boaters and boat industry professionals worldwide from nearly 80 countries have purchased David Pascoe's books, since introduction of his first book in 2001.

In 2012, David Pascoe has retired from marine surveying business at age 65.

On November 23rd, 2018, David Pascoe has passed away at age 71.

Contents